Virtual Resident Sues for Real Profits

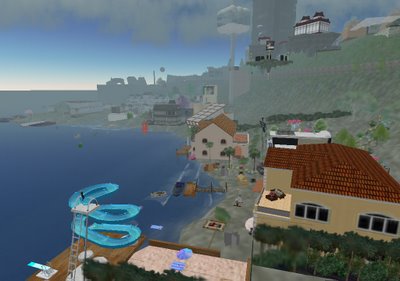

The first suit over virtual real estate has been filed in Pennsylvania. The case was filed by Marc Bragg against Linden Labs, a company which runs an online world called Second Life. SL aims to be exactly what its title suggests: a virtual world that is every bit as real as the physical. Users can create and customize a 3D avatar to represent themselves online, and there are Linden Dollars (more commonly known inworld as L$) which are used in the thriving virtual economy.

Sign up is free if you just want to look around or a mere $6 a month if you’d like to own a small plot of land and receive a modest monthly income. This isn’t to say that there’s no way to get money with a free account, though. Residents all have access to an incredibly intuitive object building system which they can use to create everything from clothing to houses to musical instruments. Once you’ve built a suit of robotic mech armor or a working light saber, other residents will pay you for a copy of it.

Bragg v. Linden Research concerns a purchase of land in Second Life at an extraordinarily low price. By entering the code for a piece of land that wasn’t for sale yet, Mr. Bragg was able to purchase parcels of real estate at auction without any competitors. He did not have to hack through any security or find a back door into a system that wasn’t online; all he had to do was change a single parameter in a web address to access a page that was online and publicly available. He argues that his purchase was perfectly legitimate; if Linden didn’t want people to purchase the land yet, then it shouldn’t have been accessible to the general public. Linden argues that he knows what he did was wrong and they are perfectly justified in banning him and confiscating his inworld property.

As a citizen of Second Life, I think this is intriguing. In SL, land is effectively server space. All the things on your parcel of land are held on computers owned by Linden Labs, but users create everything you see in SL. One of the extremely cool steps that Linden has taken (and one of the reasons I pay for my account rather than simply using a free one) is that the things I create belong to me. They are my copyright, my patent, my property; the catch is that there’s no way for me to make my own copy.

Further, there is a highly active currency exchange on which L$300 go for about $1, so when Mr. Bragg's account was suspended as punishment for his questionable real estate deal, he lost access to a lot of inworld property that has realworld value. Bragg had taken several parcels of land and built nightclubs and casinos, turning the virtual property into a healthy and active business. Now that Linden has frozen his account, Bragg claims damages in excess of $8,000, which is not unrealistic given the amount of property he owned.

Joshua Fairfield, a specialist in internet law at Indiana University, thinks this case is unlikely to set major precedent in the area of online property because the arguments will likely revolve around whether Bragg violated the user agreement. Since that agreement constitutes a contract, any breach would entitle Linden to suspend his account, realworld value or not. Irrespective of the legal issues involved, my first instinct here is to side with Bragg. Sure, he took advantage of a hole in Linden's auction system to bid on properties with no competition, but the appropriate measure is to rescind the land deal and impose some smaller sanction, not to summarily ban someone so heavily invested in the SL world.

Some of the provisions Linden has made are good common sense, like the insistence that Linden Dollars are "not redeemable for monetary value from Linden Lab." Other provisions, though helpful in regulating the SL world, are going to have to give way for virtual economies to truly take off. For example, "Linden Lab has the absolute right to manage, regulate, control, modify and/or eliminate such Currency as it sees fit in its sole discretion, and that Linden Lab will have no liability to you based on its exercise of such right."

In fact, the term "sole discretion" shows up in the agreement fifteen times. This is like the U.S. government telling you, "Our money is the only way you can pay for things in America, but we can give or take away money on a whim." Linden further reserves the right to regulate the currency exchange in any way they like. Would you invest in a country where the government reserved the right to simply take or destroy your money completely without cause?

The license specifies that "Linden Lab has the right at any time for any reason or no reason to suspend or terminate your Account.... In the event that Linden Lab suspends or terminates your Account or this Agreement, you understand and agree that you shall receive no refund or exchange for any unused time on a subscription, any license or subscription fees, any content or data associated with your Account, or for anything else."

So even though you own the content you create, Linden reserves the right to deny you access to it or even to delete it. This is intellectual property, though, so shouldn't you just regularly back up what you create so that it will be available to you if you should ever lose access to your account? Yes! But you can’t! You cannot so much as save a texture file that's embedded in an SL object, let alone save the object itself.

Once Linden takes your account, everything you built inworld is just gone, but they don't reserve the right to keep it, just the right to destroy it. In fact, they expressly limit their use of user-created content to marketing, debugging, and support. When you consider companies like Geocities and AOL own everything their users have written and posted there, this is a pretty big deal.

Bragg made a substantial amount of money from his activities inworld, and though he supplements his SL income with the money he earns as an attorney, there are some people who make their real life living entirely on SL. I understand the magnitude of having so much effort simply taken away because I own land, create content, and buy and sell virtual objects myself. The economy of Second Life, if it is to be a successful virtual economy, must not be subject to the whims of Linden; those who work and play there must have legally protected rights in the property they create.

Is the right way to do that through the courts? Probably not, or at least not yet. The owners of such virtual worlds should not be legally required to handle their residents in the same way at this vital stage in the development of the technology. The goal of Linden's project, however, is a stable virtual world which mirrors the real one, complete with a working currency exchange. By unilaterally banning people for infractions like this, they undermine confidence in the stability of the gameworld and access to the things one creates and theoretically owns.

Creating something good enough to sell on SL takes a while. The object creation system is very intuitive and easy to use, but creating anything complicated enough to sell demands an investment of time and patience. Further, creating objects that do something rather than simply looking pretty requires a knowledge of LSL, the Linden Scripting Language. For people like me with a limited background in programming, the learning curve can be pretty steep.

The amount of time I've spent learning to use the SL system and creating objects is not something I take lightly, and I only use SL for fun. If I made real money doing what I do, I would be furious. Mad enough to sue, in fact. What Linden needs to do is give its users assurances not only that the content they create belongs to them but that they will have access to it except in cases of extreme misbehavior. A fraudulent land deal can be solved with sanctions and a rescission of the contract of sale, and Linden would do well to remember its citizens are watching.

If you'd like to look me up, my name is Horatio Malaprop.

*Note: Those of you who have been following my blog will recognize this as a revised version of this article I wrote over the summer. I'm hoping Mr. Bragg will grant me another interview to let me know how his case is progressing. If and when he does, I'll get back to you with more details.

Sign up is free if you just want to look around or a mere $6 a month if you’d like to own a small plot of land and receive a modest monthly income. This isn’t to say that there’s no way to get money with a free account, though. Residents all have access to an incredibly intuitive object building system which they can use to create everything from clothing to houses to musical instruments. Once you’ve built a suit of robotic mech armor or a working light saber, other residents will pay you for a copy of it.

Bragg v. Linden Research concerns a purchase of land in Second Life at an extraordinarily low price. By entering the code for a piece of land that wasn’t for sale yet, Mr. Bragg was able to purchase parcels of real estate at auction without any competitors. He did not have to hack through any security or find a back door into a system that wasn’t online; all he had to do was change a single parameter in a web address to access a page that was online and publicly available. He argues that his purchase was perfectly legitimate; if Linden didn’t want people to purchase the land yet, then it shouldn’t have been accessible to the general public. Linden argues that he knows what he did was wrong and they are perfectly justified in banning him and confiscating his inworld property.

As a citizen of Second Life, I think this is intriguing. In SL, land is effectively server space. All the things on your parcel of land are held on computers owned by Linden Labs, but users create everything you see in SL. One of the extremely cool steps that Linden has taken (and one of the reasons I pay for my account rather than simply using a free one) is that the things I create belong to me. They are my copyright, my patent, my property; the catch is that there’s no way for me to make my own copy.

Further, there is a highly active currency exchange on which L$300 go for about $1, so when Mr. Bragg's account was suspended as punishment for his questionable real estate deal, he lost access to a lot of inworld property that has realworld value. Bragg had taken several parcels of land and built nightclubs and casinos, turning the virtual property into a healthy and active business. Now that Linden has frozen his account, Bragg claims damages in excess of $8,000, which is not unrealistic given the amount of property he owned.

Joshua Fairfield, a specialist in internet law at Indiana University, thinks this case is unlikely to set major precedent in the area of online property because the arguments will likely revolve around whether Bragg violated the user agreement. Since that agreement constitutes a contract, any breach would entitle Linden to suspend his account, realworld value or not. Irrespective of the legal issues involved, my first instinct here is to side with Bragg. Sure, he took advantage of a hole in Linden's auction system to bid on properties with no competition, but the appropriate measure is to rescind the land deal and impose some smaller sanction, not to summarily ban someone so heavily invested in the SL world.

Some of the provisions Linden has made are good common sense, like the insistence that Linden Dollars are "not redeemable for monetary value from Linden Lab." Other provisions, though helpful in regulating the SL world, are going to have to give way for virtual economies to truly take off. For example, "Linden Lab has the absolute right to manage, regulate, control, modify and/or eliminate such Currency as it sees fit in its sole discretion, and that Linden Lab will have no liability to you based on its exercise of such right."

In fact, the term "sole discretion" shows up in the agreement fifteen times. This is like the U.S. government telling you, "Our money is the only way you can pay for things in America, but we can give or take away money on a whim." Linden further reserves the right to regulate the currency exchange in any way they like. Would you invest in a country where the government reserved the right to simply take or destroy your money completely without cause?

The license specifies that "Linden Lab has the right at any time for any reason or no reason to suspend or terminate your Account.... In the event that Linden Lab suspends or terminates your Account or this Agreement, you understand and agree that you shall receive no refund or exchange for any unused time on a subscription, any license or subscription fees, any content or data associated with your Account, or for anything else."

So even though you own the content you create, Linden reserves the right to deny you access to it or even to delete it. This is intellectual property, though, so shouldn't you just regularly back up what you create so that it will be available to you if you should ever lose access to your account? Yes! But you can’t! You cannot so much as save a texture file that's embedded in an SL object, let alone save the object itself.

Once Linden takes your account, everything you built inworld is just gone, but they don't reserve the right to keep it, just the right to destroy it. In fact, they expressly limit their use of user-created content to marketing, debugging, and support. When you consider companies like Geocities and AOL own everything their users have written and posted there, this is a pretty big deal.

Bragg made a substantial amount of money from his activities inworld, and though he supplements his SL income with the money he earns as an attorney, there are some people who make their real life living entirely on SL. I understand the magnitude of having so much effort simply taken away because I own land, create content, and buy and sell virtual objects myself. The economy of Second Life, if it is to be a successful virtual economy, must not be subject to the whims of Linden; those who work and play there must have legally protected rights in the property they create.

Is the right way to do that through the courts? Probably not, or at least not yet. The owners of such virtual worlds should not be legally required to handle their residents in the same way at this vital stage in the development of the technology. The goal of Linden's project, however, is a stable virtual world which mirrors the real one, complete with a working currency exchange. By unilaterally banning people for infractions like this, they undermine confidence in the stability of the gameworld and access to the things one creates and theoretically owns.

Creating something good enough to sell on SL takes a while. The object creation system is very intuitive and easy to use, but creating anything complicated enough to sell demands an investment of time and patience. Further, creating objects that do something rather than simply looking pretty requires a knowledge of LSL, the Linden Scripting Language. For people like me with a limited background in programming, the learning curve can be pretty steep.

The amount of time I've spent learning to use the SL system and creating objects is not something I take lightly, and I only use SL for fun. If I made real money doing what I do, I would be furious. Mad enough to sue, in fact. What Linden needs to do is give its users assurances not only that the content they create belongs to them but that they will have access to it except in cases of extreme misbehavior. A fraudulent land deal can be solved with sanctions and a rescission of the contract of sale, and Linden would do well to remember its citizens are watching.

If you'd like to look me up, my name is Horatio Malaprop.

*Note: Those of you who have been following my blog will recognize this as a revised version of this article I wrote over the summer. I'm hoping Mr. Bragg will grant me another interview to let me know how his case is progressing. If and when he does, I'll get back to you with more details.